If you’ve ever bitten into a chicken breast that tastes like the Sahara Desert, or a pork chop that’s drier than your uncle’s barbecue jokes, you know this truth: moisture is king in meat.

That’s where brining comes in. But not all brines are created equal. Today, we’re diving deep into the science of dry versus wet brining, and trust me, by the end you’ll know exactly why your meat sometimes turns out juicy and other times… not so much.

Think of this as a crash course from a pitmaster who’s spent years wrestling with salt, water, and proteins – and sometimes losing to both.

The Science Behind Brining

Brining isn’t just a culinary ritual; it’s food science in action.

And at its core are two concepts: osmosis and protein denaturation. If that sounds intimidating, don’t worry – I’ll break it down like I’m explaining it to my cousin who thinks “osmosis” is a brand of hot sauce.

Osmosis: Water’s Magical Journey

Osmosis is the reason brining works. Simply put, water moves from areas of low salt concentration to areas of high salt concentration. That’s how a brine “pulls” moisture into meat.

- Wet brine: The meat is fully submerged in salty water. Osmosis drives water – and salt – into the muscle fibers.

- Dry brine: Salt sits on the meat’s surface. It initially draws water out, forming a natural brine on the surface, which then gets reabsorbed. This is osmosis doing its slow dance, quietly making your meat juicier.

Protein Denaturation: The Secret Tenderizer

Proteins in meat are like tangled up ropes. When you apply salt, these ropes start to unfold, which is what scientists call denaturation. This isn’t bad – it’s what allows meat to hold more water, giving you that tender, succulent bite.

- Salt interacts mostly with myosin, a key muscle protein.

- Denatured proteins trap water inside meat fibers, so when you cook it, it’s juicy instead of dry.

In short, brining is a two-step magic trick: water gets in, proteins lock it there.

Dry Brining: The Minimalist’s Approach

Dry brining is like the silent, understated cousin at a barbecue. No pool of salty water, just a rub of salt on the meat’s surface.

How Dry Brining Works

When you sprinkle salt on meat, two things happen:

- Moisture is pulled out initially, forming a thin layer of salty liquid.

- The meat reabsorbs this liquid, now infused with salt.

During this process, proteins are denatured, creating a sponge-like structure that holds onto water and flavors.

Why It Rocks

- Flavor explosion: Because salt is concentrated, you get intense seasoning right where it counts.

- Crispier skin: No extra liquid sitting around, which is perfect for poultry.

- Less mess: No containers, no brine solution, just a straightforward rub.

When It Struggles

- Thick cuts may not get as evenly seasoned inside.

- Requires precise salt measurement; too much and your meat tastes like the ocean.

Pro tip from the pitmaster: Let your dry-brined meat rest in the fridge uncovered for at least 12–24 hours. The skin dries out, proteins settle, and you’re rewarded with perfectly seasoned meat that’s juicy inside and crispy outside.

Wet Brining: The Classic Submersion

Wet brining is the more extroverted sibling. Meat takes a bath in salty water, sometimes with sugar, herbs, or aromatics. It’s the original way to keep meat plump.

How Wet Brining Works

- Salt penetrates the meat, thanks to osmosis.

- Proteins denature, loosening up and locking in water.

- Optional sugar and aromatics flavor the meat beyond just salt.

The result? Meat that’s evenly juicy all the way through, even if you overcook slightly.

Why Wet Brining Works Best

- Great for lean cuts: Chicken breasts, pork chops, turkey.

- Even seasoning: Salt and optional flavors spread throughout.

- Moisture insurance: You’re less likely to end up with Sahara Desert meat.

Caveats

- Can make skin less crisp (goodbye, crackling).

- Takes up fridge space and requires planning.

- Longer brine times can over-salt meat if not monitored.

Pitmaster note: Use a ratio of roughly 1 cup of salt per gallon of water for standard brining. Toss in some sugar and herbs if you want a subtle flavor layer. Keep your meat refrigerated; safety first.

Dry Versus Wet Brining: Head-to-Head

Now, let’s settle this like BBQ referees. Which method should you choose?

- Moisture: Wet brining slightly wins for thick cuts; dry brining is still juicy but more subtle.

- Flavor: Dry brining offers concentrated surface flavor; wet brining spreads it throughout.

- Texture: Dry brining gives crispier skin; wet brining can soften skin.

- Convenience: Dry brining is low-maintenance; wet brining requires space and time.

A quick pitmaster rule of thumb:

- Want juicy chicken with crispy skin? Dry brine.

- Cooking lean, thick cuts and worried about dryness? Wet brine.

Funny story: I once wet-brined a turkey and forgot it in the fridge overnight. It came out like a salt lick – lesson learned: timing and salt concentration matter.

Practical Brining Tips

Here’s where theory meets the smoker. Some tried-and-true pitmaster tips:

- Salt wisely: 1%–2% of meat weight is usually enough.

- Time it right:

o Dry brine: 12–48 hours depending on thickness.

o Wet brine: 6–24 hours; lean meats shorter, big birds longer.

- Temperature: Always brine in the fridge to stay safe.

- Flavor enhancers: Herbs, spices, sugar – they all have roles, but salt is still the star.

- Pat dry before cooking: Especially for dry brined poultry to achieve that golden, crispy skin.

Understanding the Science Without the Headache

Here’s the takeaway: brining is just smart manipulation of water and proteins. Think of osmosis as the delivery truck bringing in water and salt. Think of protein denaturation as the storage warehouse where water gets locked in for safekeeping.

Once you understand that, choosing between dry and wet brining becomes intuitive:

- Want convenience, flavor punch, and crispy skin → dry brining.

- Want even moisture, gentle seasoning, and forgiving cooking → wet brining.

You’re no longer guessing – you’re a flavor engineer.

Brining and Meat Texture: Beyond Juiciness

Brining isn’t just about keeping meat juicy – it fundamentally changes texture. Salt penetrates meat during dry or wet brining, reorganizing muscle fibers to make meat tender yet resilient.

- Dry brining: firms up outer layers, creating a crispier exterior.

- Wet brining: works throughout the meat, softening tougher cuts like pork loin or turkey breast.

- Proper brining ensures meat has a pleasant bite, not mushy.

Practical tip: a dry-brined ribeye seared over high heat develops a rich crust without losing tenderness inside.

In short: brining is more than moisture – it’s a structural makeover that balances juiciness with chew, giving meat that satisfying “yes, I nailed it” mouthfeel every time.

Sugar in Brining: Sweet Science at Work

Salt gets the spotlight, but sugar in brines adds flavor, color, and caramelization magic.

- Helps with Maillard reactions, producing a golden crust.

- Adds subtle sweetness that balances salt.

- Works in both brine types:

o Wet brines: infuses flavor layers with brown sugar, honey, or maple syrup.

o Dry brines: encourages crustier poultry skin.

Pitmaster caution: too much sugar can burn in high heat. Think of sugar as the sidekick to salt – small but essential for flavor complexity and presentation.

For home cooks and pros: adding sugar is like choosing the right wood chips – a tiny tweak that delivers huge flavor dividends.

Herbs and Aromatics: Infusing Flavor While Brining

Brining doesn’t have to be plain. Herbs, spices, and aromatics can make meat a flavor powerhouse.

- Wet brines: bay leaves, thyme, garlic, peppercorns, citrus peel infuse subtle notes.

- Dry brines: crushed herbs rubbed on meat create intense surface flavor.

- Aromatics enhance umami and complexity without overpowering natural meat taste.

Pitmaster tip: crush herbs slightly to release oils, then sprinkle or submerge in brine for maximum flavor extraction.

Bonus: aromatics make brined meat visually appealing, hinting at layers of flavor. Adding herbs lets you personalize your brine for a signature taste profile.

Brining Time: Finding the Sweet Spot

Timing is critical in brining: too short, and salt doesn’t penetrate; too long, and meat becomes over-salted or mushy.

- Dry brine: 12–48 hours, depending on cut thickness.

- Wet brine: 6–24 hours, thin cuts shorter, large birds longer.

- Thickness matters: chicken breasts absorb flavors quickly; whole turkeys may need overnight.

Pitmaster trick: check texture by touch – meat should feel slightly firmer after dry brining.

Key takeaway: mastering timing turns science into art, producing meat that’s juicy, flavorful, and perfectly seasoned instead of just salty and soggy.

Temperature and Brining: Hot vs. Cold Science

Temperature subtly influences brining. Meat should always brine cold, ideally in the refrigerator.

- Cold slows protein breakdown, allowing gradual salt penetration.

- Dry brines: benefit from chilled, uncovered rest → dries skin for crispiness.

- Wet brines: safer in covered fridge containers.

- Room-temperature brining can speed up osmosis but carries safety risks.

Think of temperature control like a slow-cooker effect:

- Too hot → proteins collapse.

- Too cold → brining takes too long.

Right temperature ensures juiciness, flavor, and safety – the holy trinity for meat lovers.

Brining Lean vs. Fatty Cuts: Different Strategies

Not all cuts respond the same to brining. Lean and fatty cuts need different approaches.

- Lean cuts (turkey breast, pork loin): benefit from wet brining to retain moisture.

- Fatty cuts (brisket, chicken thighs): dry brining suffices to enhance flavor without diluting fat.

- Over-brining fatty cuts → too soft/mushy.

- Under-brining lean cuts → dry and tough.

Pitmaster insight: tailoring brining strategies ensures predictable results, whether smoking, roasting, or grilling.

Takeaway: lean = moisture help; fatty = flavor enhancement, turning average bites into “wow” moments.

Brining Safety: Salt, Bacteria, and Storage

Brining is delicious, but it’s also a food safety game.

- Wet brines = water-rich → bacteria can grow if not refrigerated.

- Always keep meat cold, never leave on the counter.

- Use non-reactive containers: glass or food-safe plastic.

- Dry brines safer, but refrigeration still recommended.

- Never reuse brine unless boiled first.

Remember: juicy meat isn’t worth a trip to the ER. Safety-conscious brining locks in flavor, moisture, and health.

Acid in Brines: The Role of Vinegar and Citrus

Adding acid brightens flavors and aids tenderization.

- Common acids: vinegar, lemon juice, citrus zest.

- Partial breakdown of muscle fibers complements salt-induced denaturation.

- Useful for tough cuts or fish.

- Dry brines: acid as a zesty rub → flavor without overly softening exterior.

- Wet brines: citrus-heavy → fresh, vibrant note.

Balance is key: too much → mushy; too little → flavorless. Acid transforms brines into layered flavor experiences, enhancing both juiciness and taste complexity.

Brining for Smoking and Low-and-Slow Cooking

Brining shines in low-and-slow cooking, like smoking brisket or ribs.

- Salt and protein denaturation help meat retain moisture over long cook times.

- Wet brining: ensures thick cuts don’t dry out.

- Dry brining: enhances surface flavor and bark development.

- Adjust brine duration based on smoke time and wood type.

Brining isn’t just a pre-cook step – it’s part of a strategy for texture, flavor, and presentation, giving slow-cooked meat the perfect balance of tenderness and bite.

Brining Myths: What Really Works

Lots of brining myths exist:

- “Wet brining always makes meat juicier.”

- “Dry brining is just for show.”

- “You must brine overnight.”

Reality: results depend on meat type, thickness, salt concentration, and cooking method.

- Dry brining: often better for flavor punch and crisp skin.

- Wet brining: doesn’t prevent dryness if overcooked.

- Some combine dry + wet brining strategically.

Pitmaster takeaway: science beats folklore. Understanding osmosis, protein denaturation, and timing ensures meat is juicy, flavorful, and perfectly textured every time.

FAQ: Dry Versus Wet Brining and Meat Science

1. What’s the difference between dry brining and wet brining?

- Dry brining: Salt is rubbed directly onto the meat. It draws out moisture, then the meat reabsorbs it, enhancing flavor and texture. Best for crispy skin and concentrated seasoning.

- Wet brining: Meat is soaked in a saltwater solution, often with sugar, herbs, or aromatics. It penetrates the meat for even moisture retention, ideal for lean or thick cuts.

2. How does brining actually make meat juicy?

- Through osmosis, water moves into the meat along with salt.

- Salt also causes protein denaturation, which helps muscle fibers trap water.

- Result: meat stays moist, tender, and flavorful, even after cooking.

3. Can I brine too long?

Yes. Over-brining can:

- Make meat overly salty

- Change texture, making it too soft or mushy

- General guideline:

o Dry brine: 12–48 hours, depending on cut

o Wet brine: 6–24 hours, thin cuts shorter, large cuts longer

4. Should brining always be done in the fridge?

Absolutely. Keeping meat cold prevents bacterial growth and slows protein breakdown, allowing salt to work gradually.

- Dry brines: uncovered is fine → dries skin for crispiness

- Wet brines: keep in a covered container

5. Can I add sugar, herbs, or citrus to my brine?

Yes! These additions can enhance flavor:

- Sugar: aids caramelization and Maillard reactions; adds subtle sweetness

- Herbs & spices: infuse aromatic layers

- Acid (citrus/vinegar): adds bright flavor and tenderizes meat

Balance is key – too much acid or sugar can negatively affect texture.

6. Which brine method is better for lean meat vs. fatty meat?

- Lean cuts (turkey breast, pork loin): benefit from wet brining to retain moisture

- Fatty cuts (brisket, chicken thighs): usually dry brining suffices; enhances flavor without diluting fat

7. Can I combine dry and wet brining?

Yes! Some pitmasters use a short wet brine to boost moisture, followed by a dry brine to enhance surface flavor and crisp skin. This approach takes precision and timing but can yield exceptional results.

8. Will brining affect the cooking time?

Slightly. Meat absorbs water and salt, so it may:

- Take a bit longer to sear if surface is wet

- Cook more evenly internally due to moisture retention

Patting meat dry before cooking helps with bark or crust development.

9. Can brining prevent dry meat if I overcook it?

To some extent, yes. Wet brining is more forgiving, as the meat absorbs extra moisture. Dry brining enhances flavor and texture but won’t save severely overcooked meat. Timing and temperature are still crucial.

10. Is brining safe for all types of meat?

Yes, as long as you follow safety rules:

- Keep meat cold during brining

- Use non-reactive containers (glass, food-safe plastic)

- Don’t reuse wet brine unless boiled first

Proper brining locks in moisture, flavor, and safety.

11. What’s the easiest way to remember dry vs. wet brining?

Think like a pitmaster:

- Dry brining = flavor punch + crisp skin + easy prep

- Wet brining = moisture maximizer + forgiving + flavor layers

Learn the Brining Science to Make the Perfect Brisket

Brining isn’t magic – it’s science that you can taste. Dry versus wet brining both rely on osmosis and protein denaturation, but they approach the job differently.

Dry brining is a minimalist’s dream: concentrated flavor, crispy skin, easy prep. Wet brining is a moisture maximizer: even seasoning, tender meat, and more forgiving results.

Whether you’re smoking, roasting, or grilling, understanding the science behind brining transforms your cooking from trial-and-error to controlled deliciousness.

So grab your salt, decide your strategy, and brine like a pro. Because in the world of meat, moisture and flavor aren’t optional – they’re everything.

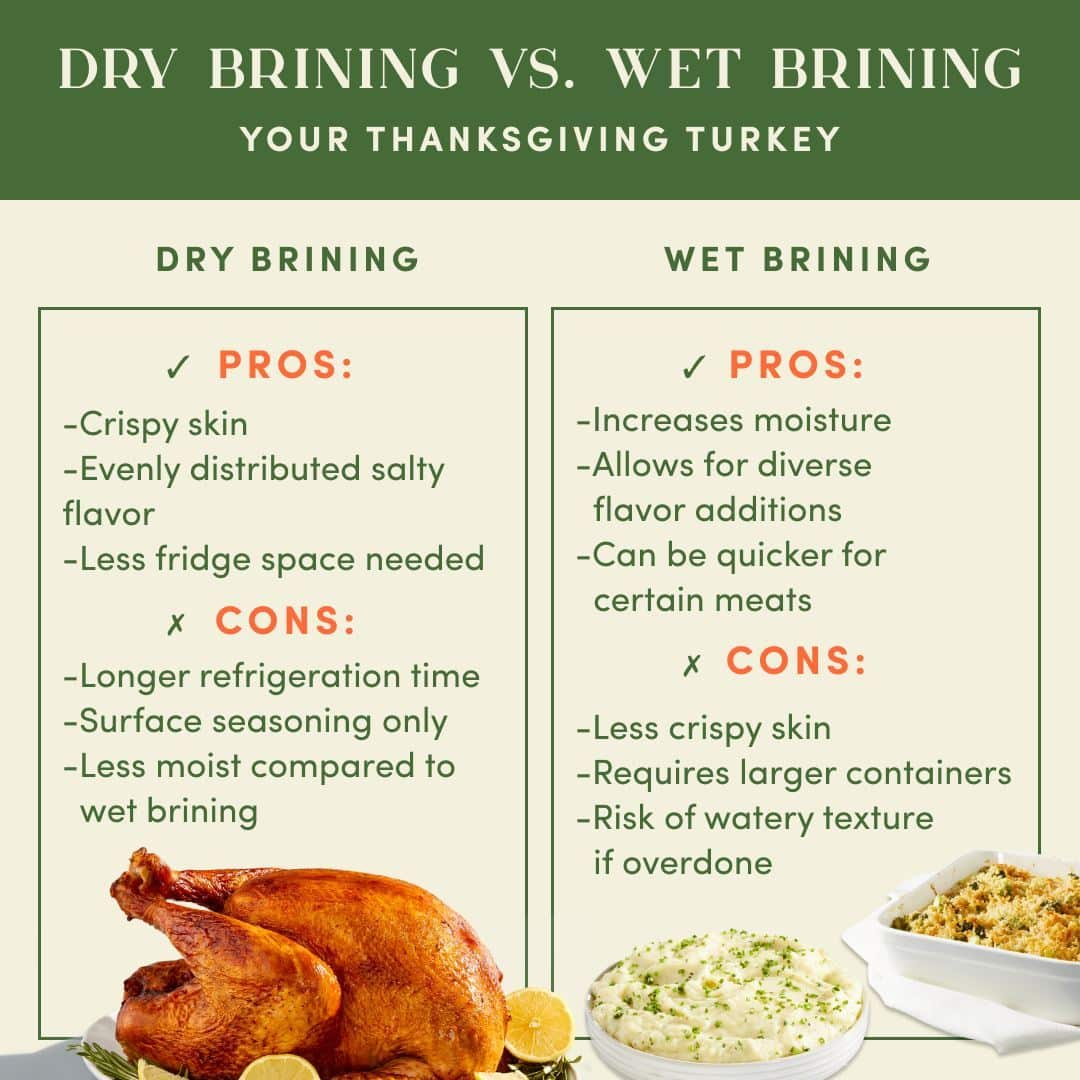

Featured image credit: @greenchef