Low, Slow, and Worth Every Minute

Barbecue’s opening act has always been Boston Butt pork shoulder and pitmasters would be BBQ divas in this case.

It’s rich, forgiving, deeply flavorful, and – most importantly – it rewards patience. This is the cut that turns backyard cooks into believers and first-time smokers into lifelong pit obsessives.

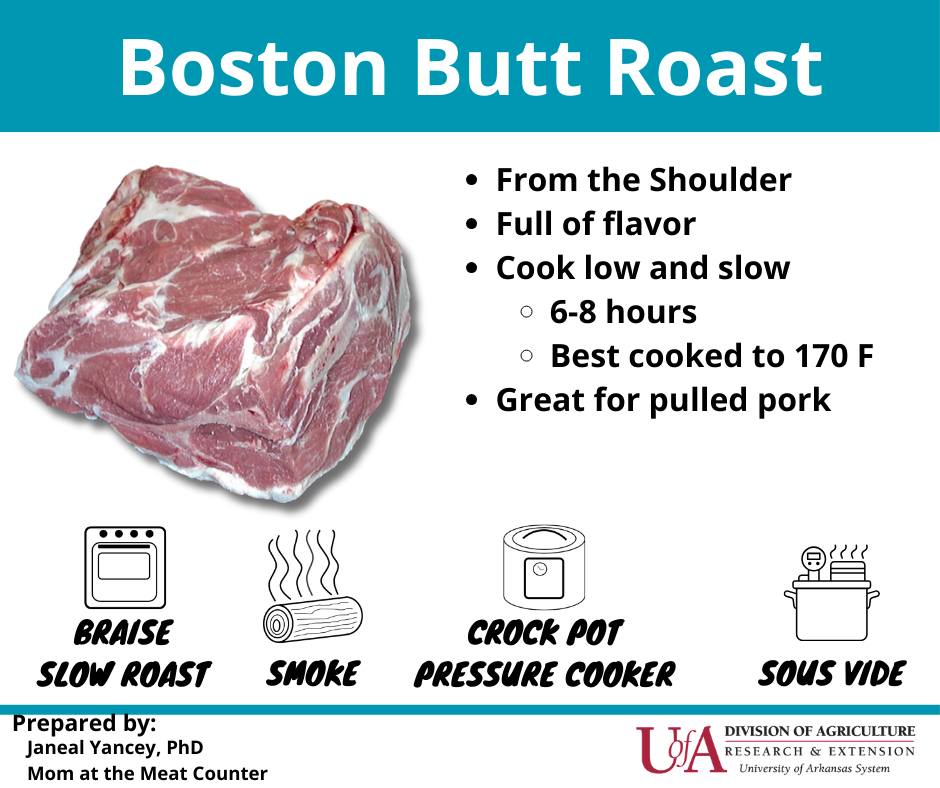

Despite the name, Boston Butt has nothing to do with the rear end of the pig. It comes from the upper shoulder, packed with fat, connective tissue, and flavor. That’s exactly why it thrives in low-and-slow barbecue.

Treat it right, and it melts into tender, pull-apart pork that tastes like you knew what you were doing all along.

This recipe isn’t about shortcuts or gimmicks. It’s about understanding the meat, respecting the process, and letting time do the heavy lifting.

Choosing the Right Wood: Smoke Is an Ingredient

Smoke isn’t just atmosphere – it’s a primary flavor component. The wrong wood can overpower pork shoulder; the right one makes it unforgettable. Boston Butt loves medium, slightly sweet smoke that complements its rich fat.

- Hickory: Classic choice, provides bold barbecue flavor without bitterness.

- Apple & Cherry: Add subtle sweetness and deepen the color of the bark.

- Pecan: Balanced, nutty, smooth, and forgiving – sits comfortably in the middle.

- Avoid strong woods: Mesquite can make pork acrid during long cooks.

- Smoke quality:

- Thin, blue smoke → builds complexity

- Thick, white smoke → builds regret

Let the fire breathe, don’t smother it with wood chunks, and remember – smoke early matters most.

Pork shoulder absorbs smoke best in the first few hours. After that, you’re just maintaining heat. Choose wisely, burn clean, and let smoke work with the meat, not against it.

Rub Philosophy: Flavor vs. Bark

A great pork rub isn’t about complexity – it’s about balance. Boston Butt already brings fat and richness; the rub’s job is contrast.

- Salt: Essential; penetrates deeply and enhances pork’s natural flavor.

- Sugar (brown or turbinado):

o Helps create dark, crackly bark

o Too much can burn during long cooks

- Paprika: Adds color more than heat

- Black Pepper: Provides backbone and bite

- Key insight: Rub seasons the surface, not the interior

That’s fine. Bark is where flavor concentrates. Skip binders unless you enjoy them; pork shoulder doesn’t need help holding seasoning. Apply rub generously, then walk away.

No massaging. No overthinking. Let moisture pull it in naturally. A confident rub builds bark, not clutter. When sliced or pulled, every strand should carry seasoning without screaming for attention.

The Stall: Where Patience Gets Tested

At some point, usually around 150–170°F, the pork stops rising in temperature. This is the stall, and it’s where barbecue teaches humility. Moisture evaporates from the surface, cooling the meat at the same rate the smoker heats it. Thermometers freeze. Time stretches. Doubt creeps in.

This is not a problem – it’s physics. You can wait it out, which builds thicker bark and deeper flavor, or you can wrap (foil or butcher paper) to power through. Wrapping shortens the cook but softens bark slightly. Neither method is wrong. What’s wrong is panicking. Cranking the heat ruins texture.

Constant poking releases moisture. Trust the process. The stall ends when evaporation slows and fat renders. Once you push past it, the meat races toward tenderness. Every great Boston Butt earns its rest at the stall – don’t rob it of that moment.

Fat Cap Up or Down: The Eternal Debate

Ask ten pitmasters and you’ll get twelve opinions on fat cap orientation. Fat does not magically baste meat as it renders – that’s a myth – but it does influence heat exposure. Fat is an insulator.

If your heat source comes from below, fat cap down protects the meat from scorching. If heat rolls from above, fat cap up can shield the surface and help retain moisture.

Here’s the real takeaway: it matters less than people argue. What matters more is trimming wisely. Remove thick, waxy fat that won’t render. Leave a thin, even layer to protect and flavor. Bark forms where meat meets heat, not fat.

Decide based on your smoker’s airflow and move on. Great barbecue isn’t about dogma – it’s about understanding your equipment and making intentional choices.

Smoker Styles and How They Change the Cook

Boston Butt is forgiving, but smoker style still shapes the outcome.

Offset smokers

- Deliver the deepest smoke flavor

- Require constant attention and precise fire management

Pellet grills

- Offer consistent temperature control

- Produce clean, mild smoke

- Require minimal monitoring

Kamado cookers

- Excel at moisture retention

- Highly efficient, making long cooks stable

Each setup affects airflow, humidity, and bark formation. Dry heat firms bark faster. Moist environments delay it but preserve juiciness. None is superior – just different. What matters is learning how your cooker behaves over time.

Track temps. Note hot spots. Adjust vents slowly. Pork shoulder rewards cooks who understand their pit’s personality. Master your smoker, and Boston Butt becomes less of a challenge and more of a ritual.

Weather Matters More Than You Think

Cold, wind, and humidity quietly mess with barbecue. Wind steals heat, forcing smokers to burn more fuel and fluctuate in temperature. Cold air slows rendering, stretching cook times. High humidity reduces evaporation, which can shorten the stall but soften bark.

Smart pitmasters plan for conditions. Use windbreaks. Preheat smokers longer in cold weather. Expect longer cooks and don’t chase temperatures aggressively. The pork doesn’t know what time dinner is – it only knows heat and patience.

Cooking through bad weather builds skill fast. When you can manage a pork shoulder in tough conditions, calm sunny days feel effortless. Barbecue isn’t just cooking meat – it’s adapting to the environment and staying steady when variables stack against you.

Knowing When It’s Truly Done

Temperature is a guide, not a finish line. Boston Butt is “done” when it’s tender, usually around 195–205°F, but numbers don’t tell the whole story.

- Tenderness is the real test

A probe should slide in with little to no resistance, like pushing into warm butter.

- Check the bone

The bone should twist freely or pull clean, a clear sign that connective tissue has fully rendered.

- Rushing ruins the result

Undercooked pork shreds poorly and eats tight. Overcooked pork dries out without proper rest.

- Rest is non-negotiable

Wrap and insulate the pork, then let it rest for at least 45 minutes.

- Why resting matters

Resting redistributes juices and completes the final internal breakdown of the meat.

Perfect doneness is sensed, not scheduled. Learn that feel, and you’ll never fear pork shoulder again.

Pulling and Serving the Pork

Unwrap the pork and remove the bone – it should slide out clean. That’s your victory lap.

Pull the meat by hand or with forks, discarding large chunks of fat.

Taste it. Then season lightly with salt or a bit more rub. Pork always needs a final touch.

Important phrase:Season after pulling, not before serving.

Serve it piled high on buns, plated with slaw, or eaten straight from the pan while standing over the counter. Sauce goes on the side. Always.

Sauce Pairings (Keep It Classic)

- Vinegar-based sauce for brightness

- Tomato-based sauce for sweetness

- Mustard sauce if you like chaos

Great Boston Butt doesn’t need sauce – it welcomes it.

Storage and Leftovers

Refrigerate leftovers in their juices for up to four days or freeze tightly wrapped. Reheat gently with a splash of liquid.

Leftover pulled pork is dangerous knowledge. Tacos, fried rice, omelets – you’ll find excuses.

Final Thoughts from the Pit

Cooking a Boston Butt teaches you everything barbecue is about: patience, control, and trusting the process. It’s not fast food. It’s slow satisfaction.

If this is your first pork shoulder, welcome to the club. If it’s your hundredth, you already know – there’s nothing quite like pulling perfectly smoked pork apart with your hands and thinking, “Yeah… I nailed that.” Fire up the smoker. The Boston Butt will do the rest.

Classic Barbecued Boston Butt Pork Shoulder

Image credit: Google Gemini

Ingredients

- 1 bone-in Boston Butt pork shoulder (8–10 pounds)

- Yellow mustard or neutral oil (binder)

- Classic BBQ dry rub (salt, black pepper, paprika, brown sugar, garlic powder)

- Apple juice or cider vinegar (optional spritz)

- Wood chunks or chips (hickory, apple, or oak)

Instructions

Preparing the Boston Butt

Start by unwrapping the pork shoulder and taking a look. You’ll see a thick fat cap and maybe some loose flaps of meat. Trim only what’s excessive. Leave most of the fat – it protects the meat and renders down during the cook.

Rub the entire Boston Butt lightly with mustard or oil. This isn’t for flavor. It’s glue. Then season aggressively. Pork shoulder is thick, and it can handle it.

Important phrase: Season like you mean it.

Massage the rub into every surface and crevice. If you’ve got time, wrap it and refrigerate overnight. If not, let it sit at room temperature for 45 minutes while you fire up the smoker. This meat isn’t fragile – it’ll forgive you.

Setting Up the Smoker

Bring your smoker to 225–250°F, running indirect heat. This is barbecue’s comfort zone – hot enough to cook, slow enough to tenderize.

Add your wood. Hickory gives bold, classic BBQ flavor. Apple is milder and sweeter. Oak splits the difference. You’re not trying to smoke the pork into submission. Thin, clean smoke is the goal.

If your smoker runs dry or hot, a water pan can help stabilize things, but it’s optional. Consistency matters more than perfection.

Smoking the Boston Butt (The Real Work Happens Here)

Step 1: The First Hours

Place the pork on the smoker, fat cap up or down – it honestly depends on your heat source, and I’ve done both with great results. Close the lid and don’t hover. The first 3–4 hours are when the meat absorbs the most smoke.

Resist the urge to poke. Barbecue isn’t a microwave. It’s a relationship.

Optional spritz after the first few hours if the surface looks dry. Don’t drown it. This is maintenance, not a bath.

Step 2: The Stall (Where People Panic)

At around 160–170°F internal temperature, your Boston Butt will hit the stall. The temperature stops rising. Sometimes for hours.

Nothing is wrong.

This happens because moisture evaporating from the surface cools the meat – like sweat on skin. The collagen inside the pork is slowly breaking down, turning tough connective tissue into silky gelatin.

Key point: The stall is not the enemy. It’s the magic happening.

You have two choices:

- Wait it out for better bark and deeper flavor

- Wrap it to push through faster

Step 3: Wrapping and Powering Through

When the bark looks dark, set, and beautiful, wrap the pork tightly in foil or butcher paper. Foil cooks faster and captures juices. Paper breathes more and preserves bark. Both work.

Once wrapped, you can bump the smoker to 250–275°F. At this point, smoke penetration is done. Now it’s about tenderness.

Step 4: When It’s Done

Forget a single magic number. Yes, most Boston Butt finishes around 195–205°F, but tenderness is the real test.

Slide your thermometer probe in. If it feels like warm butter with no resistance, it’s ready. If it still fights back, keep cooking.

Resting: The Step You Can’t Skip

Pull the pork off the smoker, keep it wrapped, and let it rest for at least 45–60 minutes. Longer is better.

Resting allows juices to redistribute and fibers to relax. Skip this step and all that hard-earned moisture ends up on the cutting board instead of in your mouth.

I’ve rested Boston Butt in a cooler for two hours and served pork so juicy people accused me of cheating.

Featured image credit: Sebastian Coman Photography