Anyone who’s logged serious hours around smokers and open flames knows this: marinades aren’t powered by feelings, they’re powered by science. They work because of science. Delicious, repeatable, slightly unforgiving science.

Every backyard cook has a story.

“I marinated it overnight and it was still dry.”

“I used lemon juice and now my chicken feels like it went through a divorce.”

“I followed a recipe exactly and Gordon Ramsay would still yell at me.”

That’s because marinades are misunderstood. They’re not sauces. They’re not brines.

They’re not magical karate training montages where Mr. Miyagi says “marinate on, marinate off” and suddenly you’re a grill master.

A proper marinade is a controlled chemical environment built around three pillars:

- Acid – changes protein structure

- Oil – carries flavor and protects moisture

- Salt – the real MVP that actually penetrates food·

Once you understand how those three work – and how they work together – you stop guessing and start cooking with confidence.

So grab a chair by the smoker. Let’s talk marinades.

What Actually Happens When You Marinate Food

First myth to kill (kindly, but firmly):

Marinades do not soak all the way into meat like a sponge.

If they did, brisket would be easy and pitmasters would be out of a job.

What really happens:

- Marinades affect the surface and near-surface layers

- Flavor penetration is measured in millimeters, not inches

- Texture changes come from protein interactions, not liquid absorption

Think of meat like a tightly packed crowd at a concert. You can influence the people at the edges, but you’re not getting to the guy in the middle unless salt is involved (more on that later).

Three scientific processes at play:

- Diffusion – small molecules (like salt) move inward

- Osmosis – water shifts across cell membranes

- Protein denaturation – structure changes, for better or worse

Different foods react differently:

- Meat and poultry = protein-heavy, slow to change

- Seafood = delicate, reacts fast

- Vegetables = cell walls, not muscle fibers

This is why a 24-hour marinade can be perfect for pork shoulder and catastrophic for shrimp.

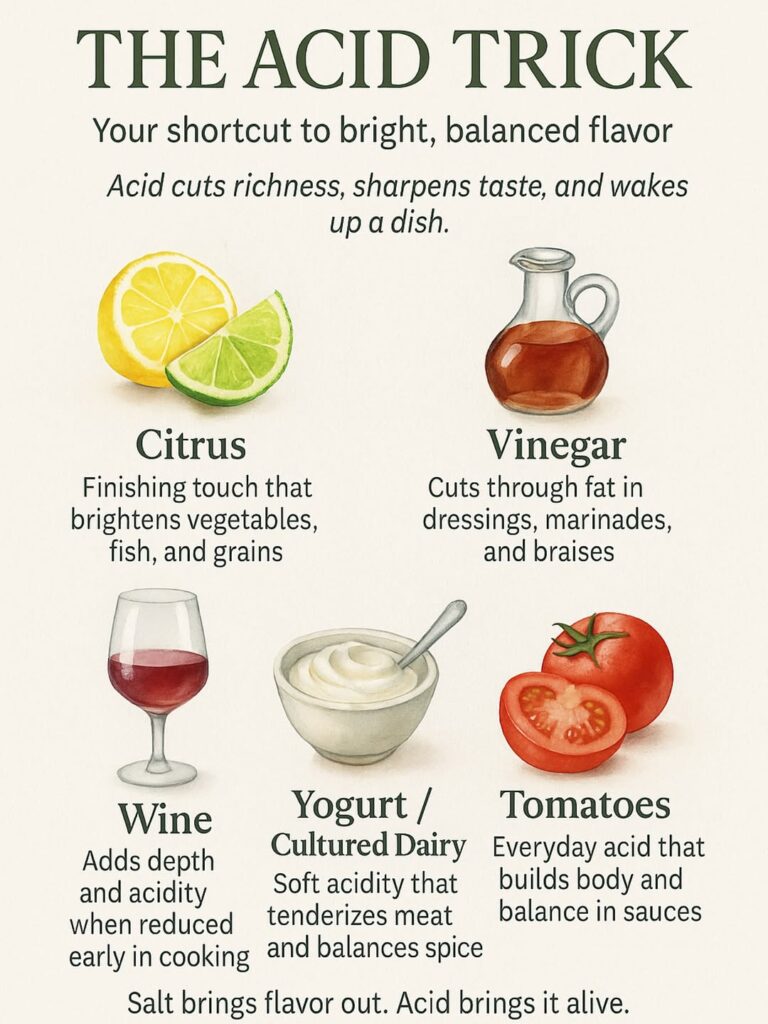

The Role of Acid: Flavor, Tenderness, and Trouble

Acid is the loud friend at the party. It shows up fast, makes an impression, and if it overstays its welcome, ruins everything.

Common acids in marinades:

- Vinegar (apple cider, red wine, balsamic)

- Citrus juice (lemon, lime, calamansi)

- Wine and beer

- Yogurt and buttermilk

- Fermented acids (kimchi juice, pickle brine)

Key point: Acid works by denaturing proteins – loosening their structure.

What acid does well:

- Adds brightness and tang

- Softens tough surface proteins

- Helps aromatics pop

What acid does badly:

- Penetrate deeply

- Tenderize evenly

- Show restraint

Leave meat in acid too long and proteins tighten after loosening, squeezing out moisture. That’s how you end up with chicken that feels like it lost a bet.

Seafood is especially sensitive.

Marinate shrimp too long and you’ve basically ceviche’d it. Delicious, yes. What you planned? No.

Pitmaster rule:

Acid is a finishing tool, not a long-term parking spot.

For long marinades, keep acid low. For short marinades, acid can shine.

The Role of Oil: Flavor Taxi and Moisture Bodyguard

Oil doesn’t tenderize. It doesn’t penetrate deeply. And yet, a marinade without oil is like Billy Batson yelling “Shazam!” and forgetting to turn into a superhero – technically functional, but missing the point.

What oil actually does:

- Carries fat-soluble flavors (herbs, spices, garlic)

- Coats the surface to slow moisture loss

- Promotes even browning during cooking

Many flavor compounds – especially from herbs and spices – won’t dissolve in water. Oil picks them up and delivers them right where you want them.

Choosing the right oil:

- Neutral oils (canola, grapeseed) for spice-forward marinades

- Olive oil for Mediterranean flavors

- Sesame oil for Asian profiles (use sparingly – it’s loud)

Key point: Oil is about flavor adhesion and surface protection, not penetration.

It’s the reason grilled food tastes grilled instead of boiled-with-attitude.

The Role of Salt: The Real Power Behind Marinades

If acid is loud and oil is smooth, salt is the mastermind.

Salt is the only marinade component that:

- Penetrates deeply

- Changes internal structure

- Improves juiciness

What salt actually does:

- Dissolves muscle proteins

- Allows fibers to retain more water

- Seasons from the inside out

This is why dry brining works and why unsalted marinades taste flat no matter how fancy the ingredients are.

Salt moves via diffusion. Given time, it travels inward, carrying flavor and moisture-retention benefits with it.

Salty ingredients that count:

- Soy sauce

- Fish sauce

- Miso

- Worcestershire

- Anchovies (trust me)

Key point:

A marinade without salt is just a scented bath.

This is where many cooks mess up – afraid of oversalting, they undershoot and wonder why the meat tastes “meh.”

How Acid, Oil, and Salt Work Together

The magic of marinades isn’t in any single ingredient – it’s in balance.

- Salt does the heavy lifting

- Acid adjusts texture and brightness

- Oil delivers flavor and protects moisture

Remove one, and the system collapses.

General ratio (not a rule, just a compass):

- More salt than you think

- Less acid than you want

- Enough oil to coat, not drown

A good marinade whispers, it doesn’t scream. Gordon Ramsay screams enough for all of us.

Why Marinades Smell Better Than They Taste (Until Cooked)

Ever notice how a marinade smells incredible in the bowl, but the raw meat tastes… underwhelming? That’s not failure – that’s chemistry waiting for heat.

Many aromatic compounds in marinades – garlic, onions, herbs, spices – are volatile. They smell amazing because they evaporate easily. But until heat is applied, those compounds stay mostly on the surface, not fully expressed.

Cooking changes everything. Heat:

- Activates Maillard reactions

- Releases fat-soluble aromas

- Transforms harsh raw notes into savory depth

That’s why raw marinades can smell like heaven but taste flat or sharp. The grill or pan is the final ingredient.

Key takeaway:

A marinade isn’t meant to taste finished before cooking. If it does, it’s probably too salty or acidic. Trust the fire – it’s doing more work than the bowl ever could.

Marinating Different Foods: What Science Says

Meat (Beef, Pork, Lamb)

- Best for tougher cuts

- Salt-forward marinades

- Acid kept low

- Time: hours to overnight

Poultry

- Benefits most from marinades

- Salt improves juiciness dramatically

- Acid used carefully

- Time: 2–12 hours

Seafood

- Extremely sensitive

- Acid-heavy marinades = short times

- Often better seasoned after cooking

- Time: minutes, not hours

Vegetables and Plant Proteins

- Oil and salt matter most

- Acid enhances flavor but doesn’t soften much

- Tofu loves salt and time

Marination Time: More Is Not Better

Let me save you some heartbreak.

Over-marination symptoms:

- Mushy texture

- Chalky mouthfeel

- Sour dominance

Food doesn’t get better indefinitely. It hits a peak and then falls off a cliff.

Rule of thumb:

- Fish: 15–30 minutes

- Chicken: 2–12 hours

- Red meat: 4–24 hours

When in doubt, marinate less and season more later.

Why Sugar Is the Most Dangerous Ingredient in Marinades

Sugar is the wild card of marinades. Used right, it adds balance, browning, and depth. Used wrong, it turns your dinner into a carbon experiment.

Sugars (honey, brown sugar, fruit juice, molasses):

- Accelerate browning

- Encourage caramelization

- Burn faster than proteins

This matters most with high-heat cooking. A sugary marinade on a screaming-hot grill doesn’t brown – it scorches.

Pitmaster rule:

- Low and slow? Sugar is your friend.

- Hot and fast? Sugar is a liability.

That’s why many competition pitmasters add sugar late, as a glaze, not in the marinade itself.

Key phrase to remember:

Sugar belongs near the end of the cook, not the beginning – unless you enjoy scraping blackened regret off your grates.

Marinades vs Brines vs Rubs: Know the Difference or Lose Control

One of the biggest mistakes cooks make is using the wrong tool and blaming the result.

Let’s clear it up:

- Marinades = flavor + surface chemistry

- Brines = salt + water + deep moisture retention

- Rubs = surface seasoning + bark formation

A marinade without enough salt won’t season deeply. A brine with oil is pointless. A rub with liquid turns into paste.

Each method solves a different problem.

If meat is dry → brine.

If flavor is bland → rub.

If surface texture and aroma need help → marinade.

Key insight:

Marinades are not replacements for brining or rubbing – they’re companions. When you stack techniques intentionally, food stops being “pretty good” and starts being memorable.

Why Marinades Behave Differently in the Fridge vs the Counter

Temperature quietly controls how marinades work – and how fast they go wrong.

In the refrigerator:

- Chemical reactions slow down

- Salt diffusion still happens

- Acid works gently and predictably

At room temperature:

- Reactions accelerate

- Proteins denature faster

- Food safety risks skyrocket

This is why recipes that say “marinate at room temp” are either outdated or reckless.

Key point:

Marinating cold isn’t weaker – it’s more controlled.

Salt still penetrates. Flavor still develops. Texture stays intact. And no one gets sick.

If you want faster results, adjust time and ratios, not temperature. The fridge isn’t slowing your marinade down – it’s keeping it from going off the rails.

Why Marinades Can’t Fix Bad Meat (No Matter What TikTok Says)

There’s a persistent myth that a strong marinade can “save” cheap or poorly handled meat. It can’t.

Marinades are enhancers, not resuscitators.

They cannot:

- Reverse freezer burn

- Restore lost moisture

- Mask spoilage

- Turn low-grade cuts into prime

At best, a marinade can improve surface flavor and texture. At worst, it highlights flaws by adding acid to already stressed proteins.

Good pitmasters start with good meat, then use marinades to amplify, not disguise.

Hard truth:

If the meat tastes bad before marinating, it will taste interesting after – but not better.

No amount of soy sauce or citrus will perform miracles. Even Billy Batson needs to shout “Shazam” first.

How Marinades Interact With Smoke (And Why It Matters)

Smoke doesn’t just stick to food—it reacts with it. And marinades change that interaction.

Moist, salted surfaces attract smoke compounds more efficiently. That’s why lightly marinated or brined meats often take on smoke faster than dry ones.

But there’s a balance:

- Too wet → smoke rolls off

- Too oily → smoke adhesion drops

- Too acidic → bitter notes intensify

Key phrase:

Smoke loves slightly tacky, well-seasoned surfaces.

This is why many pitmasters pat meat dry after marinating and let it rest uncovered before smoking. You want flavor compounds present – but not dripping.

Marinades don’t fight smoke. Used correctly, they invite it in and tell it where to sit.

Why Marinades Taste Stronger the Next Day (Leftovers Science)

Ever notice leftovers taste better? Marinades are partly to blame – in a good way.

After cooking:

- Proteins relax

- Fats solidify and redistribute

- Flavor compounds continue migrating

Salt keeps working. Aromatics mellow. Harsh edges smooth out.

This is why marinated meats often taste more balanced and cohesive after resting overnight.

Key insight:

Flavor doesn’t stop developing when cooking ends – it just slows down.

That’s also why tasting food immediately off the grill can be misleading. Give it time. Let flavors settle. Let chemistry finish its sentence.

If patience were a seasoning, it would be the most underrated one in the pit.

Marinade Myths (That Need to Die)

- “Marinades make meat juicy.”

→ Salt does. Marinades help salt work.

- “Acid equals tender.”

→ Acid equals surface change. Too much equals regret.

- “Longer means more flavor.”

→ No. It often means worse texture.

Even Mr. Miyagi knew timing mattered. Wax on too long and your arm falls off.

The One Question to Ask Before Making Any Marinade

Before mixing anything, ask this:

“What problem am I trying to solve?”

- Dry meat? → Salt and time

- Bland surface? → Oil and aromatics

- Tough texture? → Gentle acid, briefly

- Poor browning? → Less moisture, more fat

Random marinades create random results. Intentional marinades create repeatable ones.

This mindset separates cooks from pitmasters.

Mr. Miyagi didn’t just wax cars for fun. Every motion had a purpose. Marinades should too.

Final key phrase:

A great marinade starts with a goal, not a recipe.

Practical Pitmaster Tips for Better Marinades

- Salt first, acid later

- Pat food dry before cooking

- Don’t reuse raw marinades unless boiled

- Turn marinades into sauces by cooking them down

And remember: marinades are tools, not crutches.

Marinades Are Controlled Chaos

Great marinades aren’t accidents. They’re intentional chemistry guided by experience, restraint, and a little fire.

Once you understand how acid, oil, and salt actually work, you stop copying recipes and start building flavor. You cook like a pitmaster, not a contestant waiting for Gordon Ramsay to call you an idiot sandwich.

And when your food comes off the grill juicy, balanced, and unforgettable – you’ll know it wasn’t magic.

It was science.

Smoky, salty, delicious science.

Featured image credit: @chef_zouheir